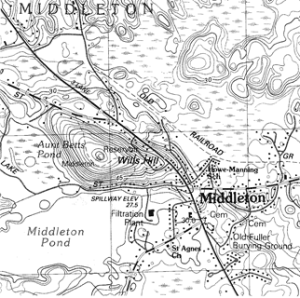

Aunt Betts Pond, circle left side of map, was formed in wake of receding glacier. An “iceberg” left behind was surrounded by sediment. When the berg melted a kettle pond was formed. Wills Hill’s contour lines in concentric ovals show it to be a drumlin. The oval hill’s long axis shows the direction of the ice movement. – Reading quadrangle USGS map

KETTLES AND DRUMLINS

Isn’t it amazing how half-mile thick glaciers that once covered this area were responsible for much of our topography? A century ago geologist John Sears1 counted 193 hills called drumlins in Essex Country. The last continental glacier, the Wisconsin, retreated from here about 11,000 years ago. In its wake, while melting, it left debris picked up by ice made plastic under high pressure2. As it slowly flowed southeast, it accumulated a massive amount of earth. Drumlins and kettles, some of the most noticeable and interesting features left behind, pock the terrain north of terminal moraines stretching from Cape Cod, Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, Long Island, on to Wisconsin, where the last continental glacier later got its name, and beyond.

What amazes us even more is that brilliant folks took so long to interpret all the now obvious signs. [pullquote]”The last continental glacier, the Wisconsin, retreated from here about 11,000 years ago”[/pullquote] Multitudes had the answers in Bibles. The flood Noah survived and similar tales were used to account for lots of land formations. We wonder what some of the hard-nosed early farmers around here thought of the mammoth boulders called erratics scattered randomly here and there across the land. They certainly knew ox teams hadn’t dragged them there. The Indians that preceded them didn’t have oxen or horses. Had they harnessed mastodons here early on? What fun it is spinning creation yarns.

Now men know there were a series of continental glaciers that waxed and waned in the ice age we are still in. Last week, Middleton’s Friday morning walking group went forth to hike on two classic glacial formations. Both lie within a half mile of the town’s center. Stream Teamers bet that 99% of the people in town haven’t visited either. The first, Aunt Betts, is a kettle pond, which Sears also called “iceberg holes.” Iceberg holes were formed from enormous chunks of ice left behind the melting glacier’s front. Sediments pouring out from under the front were deposited high around them. When the ice melted, a pond was left. According to Sears some are very deep. Thoreau’s Walden Pond is probably the world’s best known kettle. Aunt Betts is surrounded by bushy bog and stands of dead Atlantic white cedars. Just twelve years ago this area was shady red maple and cedar swamp. Beavers blocked the outflow culverts under Old Forest Street and Lake Street. The trees drowned, not able to take standing water year round. This winter, access across the swamp to the almost perfectly round three-acre pond is possible on what the walkers guessed was a good foot of ice. Ice fishermen at other area ponds say they are cutting through ice that thick and more. (A fisherman friend recently brought an old Closeteer and his wife six lovely yellow perch taken from holes through Putnamville Reservoir’s ice.) The walkers asked Red Caulfield, hunter and fisherman here as a lad, “How deep is Aunt Betts?” He answered something like “bottomless” which is the kind of story we liked about certain ponds as children. Of course we could easily find out by chopping a hole and sounding. We kind of like the idea of bottomless so probably won’t get around to it. Cutting deep holes with ice chisels is no longer easy for old timers. Even for young guys it may be difficult; we notice they use noisy motor powered ice augers.

Let’s leave imagined noise and continue on with the eighteen hikers on ice among the silent cedar trunks, high bush blueberries, leather leaf bushes, and other bog plants. Such places, untouched by humans until our group came tramping along, are crisscrossed with deer, coyote, fisher, fox and other tracks left for us to ponder. Friday the thick snow’s surface was frozen, enough to support us. This phenomenon is due to very cold nights and bright sunny days, sugaring weather. Few feet broke through in the two miles or so while walking on this winter’s several layers of snow.

The hikers, legs averaging about 67 years, may have been reluctant to leave the interesting flat bog surrounding Aunt Betts. However, no one complained as we left it upon reaching the foot of Wills Hill, a classic drumlin immediately northwest of Middleton’s center. Its summit, our destination at elevation 250-feet, is about sixteen stories above the bog ice, elevation 90, we were leaving. From bright light we climbed into the shade of a thick stand of white pines and hemlocks. The numerous tracks and scat indicated a busy deer yard. A patch of deer fur covered the dusting of new of snow received a couple days before. Three days prior to the new half-inch layer, the hike leader had seen several foot-square sheets of still bloody deer skin on the surface of older snow. A fresh gut with its several stomachs was in a frozen ball nearby. After the new snow, the day before the hike, on another practice run, he saw nothing, just the ball. Between the second trial run and Friday’s hike the coyotes must have returned to get the skin with its clinging layers of flesh. Whoever came left all the fur behind on top of the snow. Here so close to houses around the base of the half-mile long oval hill it is still wild. The seedling eating cows of yore are gone, trees have taken over. We have a photo of Wills Hill when it was treeless pasture less than a century ago. Bare Hill, where the county jail now stands, and Boxford’s well known Bald Hill are also drumlins. Both were once cow clipped as their names imply. In Sears’ geology book there are scores of photos of bare drumlins around the county. Wills Hill is far from bare now; it took us almost an hour to wend our way around trees, fallen and standing, with bushes and briars as understory, to reach the summit, a zigzag half-mile southeast from the start, the direction the glacial ice slowly flowed. It is now up to you to read about drumlin deposits of mixed boulders, gravels, sands, silts and clays. We knew of what was supposed to be beneath us from our reading and observations of pit excavations elsewhere. The old Closeteer leading the group says he has never read a satisfactory explanation as to how the glaciers formed graceful drumlins. This may be a good thing, it leaves room to puzzle.

The hardy group finally reached the top where a century ago Danvers Water Department built a no longer used pressure producing reservoir. The hardier even climbed the last twenty feet to its concrete lip and looked out across the country. Before the trees grew high, Boston and the Atlantic were clearly seen on good days.

Now just a quarter mile northwest above the square it was all down hill as we continued on the hill’s long axis. The steeper northeast and southwest sides of drumlins no longer attract us. Check for drumlins and kettles in your town. Also look for gouges and scratches in bare ledges, glacial erratics, eskers, boulder fields, boulder trains, and at whole sculpted countrysides from the tops of drumlins. Then closing your eyes look skyward; imagine two thousand feet of ice pressing down on you.

1 Sears, John Henry. The Physical Geography, Geology, Mineralogy and Paleontology of Essex County Massachusetts (Essex Institute, Salem) 1905

2 Ice at a depth of about 200-feet changes from brittle solid to plastic due to pressure. The plastic ice flows slowly outward from higher elevations. The Wisconsin glacier here moved generally southeast out from the mountains.

WATER RESOURCE AND CONSERVATION INFORMATION

FOR MIDDLETON, BOXFORD AND TOPSFIELD

| Precipitation Data* for Month of: | Dec | Jan | Feb | March | |

| 30 Year Normal (1981 – 2010) Inches | 4.12 | 3.40 | 3.25 | 4.65 | |

| 2013 – 14 Central Watershed Actual | 5.30 | 3.47 | 4.34 | 0.20 as of 3/11** | |

Ipswich R. Flow Rate (S. Middleton USGS Gage) in Cubic Feet/ Second (CFS):

For March 11, 2014: Normal . . . 110 CFS Current Rate . . . 57 CFS

*Danvers Water Filtration Plant, Lake Street, Middleton is the source for actual precipitation data thru Feb. Normals data is from the National Climatic Data Center.

**Updated March precipitation data is from MST gage.

THE WATER CLOSET is provided by the Middleton Stream Team: www.middletonstreamteam.org or <MSTMiddletonMA@gmail.com> or (978) 777-4584