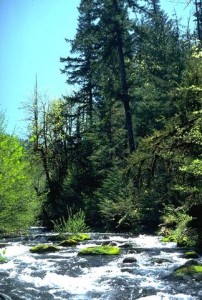

An autumn day along a stream in the Oregon Cascades, a reach constrained by bedrock and boulders covered in thick moss, the consequence of 100-plus inches of rain a year. For many years, the vertical rock face on the right, with a patch of bare rock showing, has supported a dipper’s nest on a ledge just above the typical high-water flows of spring snow melt.

Image Library of the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest

Water Closet for 12-13-13 Snorkeling

For many summers in the 70s, my sons and I would pick the hottest of the summer days to snorkel the larger streams that are tributary to the McKenzie River on the west slope of the Oregon Cascades. The tributaries are warmer than the main McKenzie in the summer, which gets much of its summer base flow from large springs fed by the snowfields and glaciers in mountains and high plateau of the Cascades. When the main McKenzie might be in the mid to high 50s in July and August, the tributaries are 10 degrees warmer, or more.

These small rivers, called creeks in the Pacific Northwest, are crystal clear at that time of year; high-gradient streams that tumble over riffles, runs and cascades with the occasional waterfall that we’d “portage around”. We’d leave a car downstream and have someone drop us off three to five miles upstream. Wearing old sneakers and t-shirts to protect toes and chests from the rocks and boulders, we’d don face masks and start floating downstream looking for cutthroat, rainbow and bull trout, mountain whitefish, sculpin, crayfish, otters, merganser and harlequin ducks, dippers, great blue herons, ospreys and whatever else was in or near the water. We’d try to stay abreast to cover the stream, pointing out things to each other with grunts.

Even on the hottest days, the water was cold enough that you had to pull out every few minutes and sit in the sun for a few minutes to warm up. We did not have wet suits. If you pulled out of the water quietly and slowly sat down you’d often have the local blacktail deer eye you for a couple of minutes and then go back to feeding and drinking. Out of the dozens of drifts, we probably encountered black bear and elk only three or four times, but they, like the blacktail, seemed unafraid of anything swimming, coming out of the water.

A good example of a stream in the Oregon Cascades on a small floodplain where the channel is free to move around. The boulders providing channel structure along this reach are eight to twelve feet in diameter, and the tall conifers on the right are old-growth Douglas-fir, eight-plus feet in diameter, well over 200 feet tall, and over 450 years old.

Image Library of the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest

I especially enjoyed watching the dippers or American water ouzels feeding. These robin-sized chunks of charcoal would plunge into the water and literally flap their wings to “fly” down to the bottom to feed on snails and aquatic insects, popping back to the surface to swim or fly to a rock where they’d smash open the snail or caddis fly case. Watching their aquabatics from a trout’s-eye view was always fun. And being in the cold water, you could really relate to their dipping behavior, easily imagine them thinking, “Wow! That’s cold! Man! That’s cold!”

The trout would almost always be facing upstream, so that as you floated toward them they’d see you coming, swim up to investigate and then dart off, providing good views of their beauty — and info as to where they liked to sit in the complexity of the stream channels, waiting for food to drift toward them. Welcome data for future fly fishing trips. The biggest ones were often the most bold to anything coming at them underwater, swimming close before zooming away. When we were drifting next to each other in the deeper pools, they often squeezed between us in their escapes, providing great views. For my older son, who was an avid fisherman, these were the highlights of most drifts. He’d shoot to the surface and you could hear him saying things like, “Did you see that one? It must have been five pounds! In this little creek!”

A few times, we were underwater witnesses to an osprey catching a fish. These were heart-stopping events as you’d be watching the trout when a big splash suddenly exploded the water a few feet in front of your face mask. If you didn’t bolt upright in fright, you’d be staring at a tangle of legs and wings in a screen of bubbles while a squirming fish wrapped in talons was being hauled out of the water. I’m pretty sure we pulled out and sat in the sun talking about what we’d seen every time it happened.

A couple of times we encountered small groups of otters. One time they turned and were gone back downstream in a flash and we didn’t see them again. Another time they were very curious, and if we stayed face down in the water, would approach to within a few feet to check us out. One caught a trout and shared it with another up on a stream bank as if we weren’t there. After a few minutes, they decided to head downstream and we saw them again two or three more times that afternoon, playing in the biggest pools.

The great blue herons we saw almost always acted as if we were not there, remaining totally focused on their stalks. As we came closer, they seemed to sigh deeply, turn and look at us, shake their heads in seeming disgust and fly off to another pool. Amusing but uneventful encounters.

We usually encountered harlequin ducks, sea ducks that nest inland along relatively undisturbed streams. If it was early in the summer we might encounter a hen plus ducklings floating and tumbling their way downstream. Going faster than we were, they’d hurry on past us as they searched for food. We might see them an hour or so later flying back upstream for another pass.

These were fun and memorable times. They’re always mentioned at family reunions, but none of my older son’s daughters have ever expressed interest in doing something like this. They live in the south where streams are not especially inviting with alligators and cottonmouths swimming around in them. I remain hopeful that my younger son’s daughters will join me sometime.

————————————————————————————————-

THE WATER CLOSET is provided by the Middleton Stream Team: www.middletonstreamteam.org or <MSTMiddletonMA@gmail.com>